In April this year, I travelled to Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh for the Buyer-Seller Meet organised by APEDA and NERMAC, an effort to directly connect farmers with major buyers. It took me two full days by road to reach Tawang, a journey that could have been completed in just 45 minutes by helicopter. That contrast sums up Arunachal Pradesh: a land rich in potential but held back by weak infrastructure. What I saw was a lesson in how geography, connectivity, and agriculture intertwine.

Day 1 – The Starting Point

On April 8th, I caught the 9 a.m. flight from Delhi to Guwahati, Assam. I spent the evening meeting with Food Corporation of India officers who spoke candidly about the challenges of food distribution in the Northeast—long distances, tough terrain, and inadequate transport facilities.

Day 2 – Into the Hills

We left Guwahati at 11 a.m. for the 10-hour drive into Arunachal Pradesh. The transformation was striking. Lush paddy fields gave way to subtropical forests, and as we climbed above 5,000 feet, the landscape shifted to pine-covered slopes.

We pushed through lunch and deeper into the hills, passing Bomdila at 8,000 feet, where neat wooden houses sat surrounded by gardens in full bloom. Women labourers, some with babies tied to their backs, worked on road construction—a scene that captured both the region's beauty and the quiet resilience of its people. The contrast was striking. Pristine mountain villages on one side, and on the other, the arduous work of building the very infrastructure that could transform their livelihoods. By the time we reached Dirang, exhaustion had set in. I kept thinking: if it takes this much effort for us to arrive, what must it mean for farmers trying to move their produce?

Day 3 – Tawang and the Buyer-Seller Meet

I woke up before sunrise to mountain views from Dirang and set off for the final stretch to Tawang. Crossing the Sela Tunnel at 13,800 feet, one of the world's highest road tunnels, felt symbolic. This single piece of infrastructure has already cut travel time to Tawang significantly. It showed me how one intervention can change the rhythm of an entire region.

We reached Tawang after four hours and rushed to freshen up before the event.

At the meet, buyers had come from across India. Many farmers had travelled for two full days from remote corners of Arunachal. The irony wasn't lost on me: it took them the same time to reach Tawang as it took us coming from Delhi. This absurdity perfectly captures Arunachal's connectivity crisis. Their stories echoed the same frustration: slow, unreliable, and costly transport. Yet the produce was exceptional, with kiwi, apples, large cardamom, ginger, and oranges, to name a few.

Arunachal is a default organic state, and as the largest kiwi producer in India (accounting for nearly 40% of India’s kiwi production), its horticultural goods could command premium prices in growing domestic and international markets. At the same time, India has just concluded a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with New Zealand that will gradually open Indian markets to a larger volume of imported kiwi. This emerging trade landscape makes Arunachal’s infrastructure gap—cold storage, reliable road and rail connectivity, and efficient transport—even more urgent to address, because without them its farmers will struggle to compete on price and speed, regardless of their organic advantage and superior production volumes.

One buyer shared candid insights: with no central processing or quality checks, procurement becomes costly and chaotic. Transport alone costs around Rs. 10 per kilo by truck, and the absence of organised supply chains means larger farmers often buy cheaply from smallholders and sell at a premium. By sourcing directly from small farmers, he believed costs could drop, benefiting both producers and buyers. He was particularly interested in large cardamom from Lohit district, which offers a uniform variety unlike other districts where farming is unorganised. But the logistics were daunting: while it takes just 5 days to move produce from Meghalaya to his factory in Noida, it takes 10 days from Lohit. This delay, plus the added costs, makes procurement commercially unviable without transport subsidies from the state.

Even buyers from the neighbouring country, Bhutan, admitted preferring West Bengal over Arunachal. The reason? It is cheaper and easier to move produce into Bhutan from West Bengal than from Arunachal Pradesh, even though both states share a border with Bhutan.

Without collection centres, cold storage, and reliable transport, buyers are forced to spend days and extra money to source produce. That's not a model for scaling agricultural trade.

Day 4 – A Glimpse of Culture, Then Back to the Road

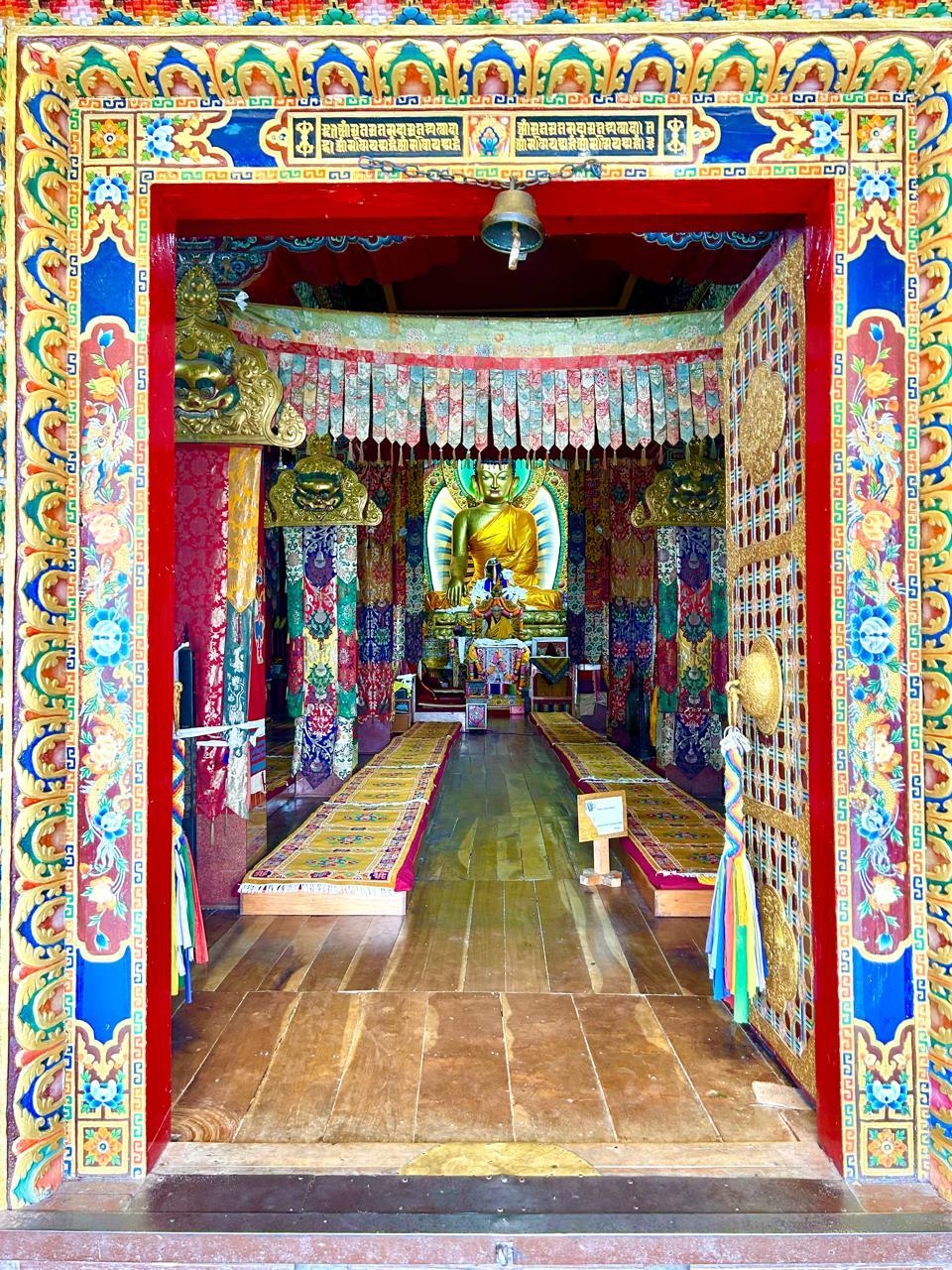

On April 11th, before leaving Tawang, I visited the serene Tawang Monastery, just five minutes from our hotel. The air was crisp, prayer flags fluttered in the wind, and the monastery's golden roof glistened against the snow peaks.

I had hoped to visit the Bum La Pass, a high-altitude crossing near the Indo-China border, but our schedule didn't allow it. This pass, if better utilised, could be a vital trade link for Tawang, potentially opening up faster movement of goods and even creating cross-border economic opportunities down the line. I picked up local spices before we began the nine-hour journey from Tawang to Tezpur in Assam, winding down from alpine forests into subtropical valleys.

Day 5 – Home, Eventually

From Tezpur, we drove to Guwahati Airport, only for the flight to be delayed three hours. By the time we landed in Delhi, it was 8 p.m. Two full days of driving for a journey that a helicopter could cover in under an hour.

The Bigger Picture – Why This Matters for Agriculture

This trip left me with one certainty: Arunachal Pradesh has the produce, the organic advantage, and the ambition. What it lacks is the infrastructure to deliver. Three urgent investments stand out:

- Collection Centres: Buyers should be able to fly into one hub and access produce aggregated from across the state. The state lacks even basic infrastructure for sorting, grading, or packaging. Farmers are forced to sell immediately after harvest at distressed prices. Strategic aggregation centres at locations like Pasighat, Dirang, and Roing, equipped with sorting, grading, and pre-cooling facilities, would allow buyers to access produce from multiple districts without spending days travelling between remote farms.

- Cold Storage & Processing: High-value crops like kiwi, ginger, and apples need preservation to retain freshness and value. Arunachal has only two cold storage facilities with a combined capacity of 6,000 metric tonnes, the lowest among the Northeastern states. Compare this to Assam's 43 facilities holding over 2 lakh metric tonnes. Without cold chains, kiwis from Ziro take 12-16 hours to reach Guwahati in non-refrigerated trucks, leading to massive spoilage. The lack of processing infrastructure also means oranges are exported to Bangladesh for processing and re-export, a value that should stay with our farmers.

- Transport Connectivity: Strategic tunnels, all-weather roads, and short air links can turn two-day journeys into a matter of hours. The Sela Tunnel has already proven this, cutting travel time to Tawang significantly. But roadways remain the only real option, with rail connectivity minimal and air cargo services limited despite the new Donyi Polo Airport. When transport alone costs Rs. 10 per kilo from Lohit and takes 10 days, compared to just 5 from Meghalaya, Arunachal farmers simply can't compete.

When I look back at the photos of serpentine roads, snow-capped passes, bustling market halls, I see more than just memories. I see a roadmap. If we follow it, Arunachal's farmers won't just grow treasures in hidden valleys; they'll have the means to bring them to the world.